Murray Stein, Ph.D.

INTRODUCTION

The theme of individuation sounds through Jung’s writings, like a leitmotiv, from the time of his break with Freud and psychoanalysis onward without pause to his death. All things considered, it is perhaps his major psychological idea, a sort of backbone for the rest of the corpus.

Introducing the term in his esoteric, anonymously published little book Septem Sermones ad Mortuos (Seven Sermons to the Dead) in 1915, Jung deepened and expanded the idea in the much revised work, also begun in the same period, Two Essays in Analytical Psychology (Coll. Wks., Vol. 7) and in the summary work of the early period, Psychological Types (Coll. Wks., Vol. 6). Later he added further substance to the notion in his studies of archetypes and especially in his researches on alchemy. He detailed individuation clinically in his seminars (Dream Analysis, The Visions Seminar, and Nietzsche’s Zarathustra) as well as in several case studies. It also played an important role in his many writings on religion and culture.

Individuation was taken up as a central theme by nearly all of Jung’s important students. Major contributions were made to the theory by Fordham, who studied individuation in children, and by Neumann, who saw individuation as unfolding in three major stages, each containing several sub-phases. Hillman, a Jungian deconstructionist, has vigorously attacked the notion of psychological development in general and individuation in particular, holding a view that such ideas are nothing but fantasies used to construct modern psychological myths. More recently, Jacoby has added refinement and differentiation to the theory of individuation by introducing data from modern infant research. Samuels has introduced the feature of political consciousness and involvement. The debate goes on.

In the following pages, I present a distillation and synthesis of the Jungian tradition on the central theme of individuation, situating this particular discussion in the clinical setting of psychotherapy and showing how the working Jungian psychotherapist may use this developmental idea in practice.

*

When Jungian psychotherapists face patients for the first time, they try to size them up. One listens to that first outpouring of narrative, of confession or complaint, with an ear cocked to tone. Does this sound like true suffering, or is this person blocked in feeling or cranky in thought? Is this someone who blames others too much, or does she shoulder too much responsibility for what goes wrong? Is this person too passive? Too active?

Within the texture of even the most innocent first narrative therapists will often spot fragility, entitlement, emotional vulnerability and a host of other telling feelings and attitudes. In the therapist’s own emotional responses to this narrative, too, one may detect the pull of a raging demand for help, or the opposite – the pushing away that creates too great a distance. In the first sessions, and indeed throughout a long therapeutic treatment, therapists spin an evolving mental assessment of how their patients are carrying on with life at the particular stage they find themselves in now, as they attempt to settle their old accounts, open new ones, and elaborate their stories.

Jungian psychotherapists hold a notion of psychological development, of “stages of life,” and we ask ourselves questions about the levels of psychological development demonstrated in the narratives offered by the people who come to us. Does a person’s discourse show a good match, we wonder for instance, between chronological age and psychological attitudes? The full clinical impression of a person’s level or degree of psychological development takes many sessions and much observation to formulate in depth and detail. It is an estimate of their achieved individuation.

The Jungian therapist’s unspoken reflections on achieved individuation take place within the general context of formulating a diagnosis and assessment of a patient’s psychological development. What is the patient’s level of everyday functioning? Does physical illness play a role? Is there serious psychopathology? Sometimes these considerations feature prominently in the treatment; in other cases they play no significant role at all. Determining their importance for guiding treatment is the business of the early sessions of psychotherapy, even while these concerns remain a consideration throughout. And just as diagnosis from the clinical perspective of the standard Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DMS IV) is an ongoing and evolving consideration — which the Jungian psychotherapist, like any other, makes in such terms as major depression, anxiety, the various character disorders, not to mention addictions, relationship and adjustment problems, etc. — so also the evaluation of individuation is an evolving business. It is not always so clear exactly where a particular patient stands on the road to individuation even after considerable time has been spent in therapy, but the experienced Jungian psychotherapist will have a strong sense of the general picture after even a few sessions.

This question of how far a person has come on the road toward individuation is different from the usual types of diagnostic question raised in psychological assessment, although they are not unrelated, as I will try to show in the following pages. In considering individuation, one has in mind something more encompassing than only cognitive development, behavioral adjustment, moral attainment, or the presence or absence of psychopathological features. These are important markers in the complexity that constitutes individuation, but they are not exhaustive. There are other features that are also determinative. The assessment of individuation describes a person’s conscious and unconscious assumptions and attitudes: about the basis and sources of identity and sense of self worth, about the quality and meaning of relationships to other people and to the world at large, about the energy (or the absence of it) poured into personal striving and ambition, about the objects of desire and passions that lead a person into the highways and byways of life, about the focus of life’s meaning. What the Jungian therapist is looking for in making an assessment of individuation is how a person’s chronological age matches up with the level of development in these conscious and unconscious assumptions and attitudes. To take the full inventory of them is a large and complex study, which includes transferential and countertransferential sources of information. Of course, cultural factors must also be considered in making a reasonably fair and accurate assessment of a person’s individuation.

Jung himself, who is generally credited with being the first important full lifespan theorist, wrote about two major stages of life, the first half of life and the second. Each stage has its typical developmental tasks, sequences and crises. A later Jungian theorist, Erich Neumann, conceptualized the lifelong development of personality as falling into three major eras or phases. Neumann’s paradigm, which does not contradict Jung’s, adds a useful degree of further differentiation to the first half of life, and Neumann’s model is widely used by Jungian psychotherapists today.

Within the linguistic universe of analytical psychology, the lifelong development of personality is called individuation. Briefly stated, individuation refers to the process of becoming the personality that one innately is potentially from the beginning of life. The sequence of developmental stages in almost every individual’s life has common features, hazards, and breakdowns. The Jungian psychotherapist has a keen awareness of how this developmental sequence unfolds ideally and how it so often fails to reach its proper destination due to genetic, circumstantial, social, and cultural obstacles. There are also some important differences between the genders to be considered.

In summary, then, the patient arriving for Jungian psychotherapy is intuitively and clinically assessed in the mind of the psychotherapist, generally against the DSM IV standards of normal and abnormal mental and psychological states and specifically against the perspectives of the individuation process as this has been outlined in the Jungian literature (see References for a selection of key works on this topic). Most likely this assessment never becomes apparent to the patient, nor is it discussed explicitly. It is, however, used by the therapist to guide interpretations, to make interventions, and to establish and maintain the structure of therapy. Much of the therapist’s style in a specific case depends on this assessment of where the patient stands on the road of individuation.

In the following pages I will survey the three main stages of the individuation process, its two major crises periods, and its ultimate goal. The efforts made in therapy are fundamentally geared toward promoting and facilitating, or toward unblocking and restarting, the individuation process in patients. The three stages of individuation are: a) the containment/nurturance (i.e., the maternal, or in Neumann’s terminology the “matriarchal”) stage, b) the adapting/adjusting (i.e., the paternal, or, again in Neumann’s terminology, the “patriarchal”) stage, and c) the centering/integrating (in Neumann’s terminology, the individual) stage. (These can be coordinated with Erik Erickson’s seven stages of psychological development.) The two major crises of individuation fall in the transitions between these stages, the first in adolescence and early adulthood and the second at midlife.

These three stages should be thought of not as discrete and entirely separate rooms that are inhabited for a period of time and then left behind when one enters the next chamber, or as a specific number of miles on life’s journey never to be trodden again once passed through. Rather, they indicate emphases and predominant attitudes during the major eras of a person’s life. They are stages of growth and development that shade gradually from one into the next, and features of each continue, but in a less predominant way, as a person makes the passage through a whole lifetime. The first stage refers to childhood, the second to early and middle adulthood, and the third to middle and late adulthood and old age. This view of the lifeline is a tool for psychotherapy, useful if applied with a deft touch but damaging if handled too concretely and with blunt force. It is a perspective that gives the Jungian psychotherapist a way of understanding the psychological qualities and some of the troubling deficits of the patients who come for treatment.

THE CONTAINMENT/NURTURANCE STAGE OF INDIVIDUATION

Like other mammals, humans start terrestrial life in a maternal womb. This space, bathed in amniotic fluid and kept warm by the surrounding body of the mother, is the archetypal nurturing environment. Passively fed through the umbilical cord, the fetus is required to make little effort to care for itself. For postnatal life, the mother’s womb symbolizes the psychological environment needed for the first stage of a person’s life. It is a protected space, an enclosure in which the vulnerable young can grow relatively undisturbed by toxic intrusions from the surrounding world. For humans, this type of shielded environment is suitable for a lengthy period of time after birth. This is true especially for infants, for unlike many other mammals, human offspring, because of their large head size, are ejected from the mother’s womb long before they are prepared to function independently of a nurturing container. Human neonates require an external nurturing environment of extended duration, until their bodies and minds are prepared to cope with the physical and social worlds into which they have been delivered.

Especially in modern first world cultures, this first stage of life, which we casually refer to as childhood, lasts a long time. For most people today, the containment/nurturance stage extends through much of the educational experience, from infancy and the years of primary and secondary school, through university studies and further professional training. During these years, a person, even if physically and to some extent psychologically prepared to assume some of the roles of adulthood, is not fully equipped to deal with the demands of social life and is usually not economically viable as an adult member of society. This period of dependence on parents and parental institutions may last for 30 years or more. In traditional cultures, on the other hand, where initiation rituals into adulthood occur at around the age of 12 or 13, the containment/nurturance stage of individuation is typically terminated at the onset of puberty. By that age, a person is considered ready and able to take up the physical and cultural tasks required of young adults in the group. There it is an abrupt and dramatic change of attitude and social identity; in our modern cultures, the change is gradual and takes place over decades.

The quality of the containment/nurturance stage is defined, symbolically speaking, as maternal. The containing environment is constructed socially and psychologically on the model of a womb, in that the basic ingredients needed for survival – food, shelter, highly structured settings of care that are screened and protected – are provided by family and society. At the emotional level, nurturance is delivered (ideally) in the form of warm support and encouragement. Young children are loved unconditionally, appreciated for being rather than doing. The harsh aspects of reality are screened out. Children are held, caressed, and comforted by smiling, doting parents who stand guard over them and look out for their well-being. The most that is asked of the young is a cooperative and willing attitude. For the rest, adult supervision and protection prevail. Not much is demanded of young people at this stage in the way of contributing to the general welfare of the family or group. They remain dependent and are nourished by parents and other adults.

Naturally the degree of richness of the matrix in this stage of containment is highly dependent upon the attitudes and resources that happen to be available to the adult caregivers. It is also crucially dependent on their emotional stability and maturity. Instead of screening harsh reality out of the protected environment, anxious parents may amplify threats and worrisome aspects of reality. Absence of adequate containment and serious breaches in the walls of protection surrounding the person at this stage generally put down the groundwork for later psychopathology, such as anxiety disorders and various character disorders. In addition, the frightened or threatened child, in order to replace the absent or breached outer protective shield, develops primitive and massive defenses of the self, which also have the capacity to cut the person off from important developments and relationships later in life.

Under the best conditions, the quality and degree of containment gradually changes as a person passes through the sub-phases of childhood. At first there is maximal nurturance and containment. The kind of attention given to the newborn baby, who can do practically nothing for itself, modulates to a less intense level of care as the child grows older. Later the parents will place further limits on the amount and kind of nurturance they provide, and the degree of containment is eased. Expectations for a relative amount of autonomy, independence, and self-control are introduced at many points along the way, as the child is able to respond positively to these changes. Normally these shifts are met by a willingness on the part of the child to cooperate if the onset of these new conditions corresponds to growing abilities (cognitive, emotional, motor). As the individual proceeds through the usual sub-phases of childhood development, the nurturing container evolves in order to meet the new needs that appear and to reduce what would become an intrusive type of overprotective care in many areas. By the end of this stage of individuation, people experience only a minimum of nurturing and containment from the environment and are able to do for themselves what others have done for them earlier.

The first and primary nurturing figure is, of course, the mother. From pregnancy onwards, the mother symbolizes the nurturing container itself. Nurturing and containing can be referred to as “the mothering function,” whether this is delivered by the actual biological mother, by mother surrogates, by fathers, teachers, or institutions. Symbolically speaking, they are all “the mother” if they approach the individual in a nurturing, containing mode.

Nurturing, while it grows out of concrete acts of mothering like breast-feeding, is not only physical, and to a large extent it takes on other features as the child grows. Feeding takes place on emotional, cognitive, and spiritual levels. Nurturing is an attitude. Symbolically it has been expressed by mother figures since time immemorial. The Great Goddesses of world religions – figures such as Demeter (Greek), Isis (Egyptian), the Virgin Mary (Christian) to name only a few – are identified as nurturers, feeders, containers, and comforters. The role of the Great Mother Goddesses extends far beyond the biological and physical feeding functions, although it is rooted in the gestures and rituals of literal feeding. The church, for example, is a classic nurturing, containing institution that feeds its “children” the bread of heaven, a spiritual type of food. Its primary mission is not to feed people materially, although sometimes it has done so and has dedicated itself to the material improvement of the poor. Yet its main meal is a symbolic one. Nurturing institutions are typically represented by mother images. Similarly, containers such as ships are referred to as “she.” This does not mean that actual mothers or nurturing institutions like the church or ships of the navy do not also have marked fatherly, patriarchal functions and aspects, but when the emphasis falls on nurturing, the images hark back to the mother. Therefore this stage of individuation is referred to as the mother stage, and people within it are seen as living “in the mother.”

Whether the containing/nurturing function is performed by the actual mother, by another person, or by an institution, the underlying attitude is: “I am here to help you.” Nurturers are providers, helpers, sustainers. This attitude on the part of the nurturer, in turn, creates or inspires a corresponding attitude in the recipient of nurturance. Nurturers conjure children, and children attach themselves to nurturers. The recipient’s attitude is one of radical dependence upon the perceived nurturer. This attitude may be quite conscious or largely unconscious. In the first years of life, it is definitely unconscious. Nurturance and containment are simply taken for granted by the infant and the young child. Recipients often struggle mightily against their caregivers, not realizing how profound the real dependence actually is. A child pushing away from its mother and running impulsively out into traffic simply assumes, at an unconscious level, that it will be safe, cared for, protected, and at the end of the day fed, held and comforted. This degree of entitlement is unchallenged in the young child, and the nurturing adult, who may even find it attractive and mildly amusing, freely gives it. The dependency arising out of a good bonding between infant and mother is to be desired, for too much anxiety about the world at this early stage of life would not augur well.

The containment/nurturance phase of individuation serves the psychological purpose of supporting and protecting an incipient ego in the child. The ego complex, which we conceive of as the center of consciousness with certain executive functions and some measure of innate anxiety about reality, comes into being gradually over the course of early childhood. Its earliest beginnings lie already in the intrauterine experience. There the ego is barely a point of awareness and of reaction to stimuli, a tiny bit of separate consciousness in the darkness of the mother’s body. With birth, the ego’s world is dramatically enlarged, and the infant’s ego responds by registering and reacting to sights, tastes, and touching as well as to sounds and smells. Very quickly a baby is able to recognize its mother’s face and to respond. At a profound psychological level, however, infant and mother remain joined in a state of psychological fusion. The ego’s separateness is severely limited. This unconscious identification is mutual. The mother is as deeply tied into it as the infant. Jung termed this type of identification participation mystique, a phrase that denotes an unconscious psychophysical bond. What happens to one person in this union happens to the other. They feel each other’s pain, hunger, and joy. For the infant, this forms the basis of later empathy and eventually will develop into a sense of responsibility for others and an inner conscience. It also creates part of the foundation for later ego identity, especially for female children.

With further motor and cognitive development, the ego is able to begin exercising its executive functions and to exert some control over muscles. Arms and legs become coordinated and speech follows. Soon the whole world becomes a vast theater of play and learning, a veritable Garden of Eden to explore. The healthy child asserts itself vigorously and with abandon in this perceived safe and protected environment. Serious reality testing is left to the oversight of the parental unit, a nurturing and containing presence hovering above. The boundaries of this paradise are tested soon enough as the child exerts more and more autonomy physically and emotionally. Disobedience and increasing consciousness go hand in hand. Psychological boundaries begin to be erected between child and parental guardian, and the child becomes aware of the differences between self and other and exploits them. Throughout this stage, however, a basic level of unconscious identification remains between child and nurturing environment. Participation mystique continues to reign. Jung thought of the child’s psyche as largely contained in the parental psyche and reflective of it. The child’s true individual personality does not emerge until it leaves the parents’ psyche in a sort of second birth, a psychological birth for the ego when it becomes a more truly separate entity.

This psychological containment of the young gives parents enormous influence over their children, not only through the conscious transmission of culture, tradition, teaching and training, but more importantly and deeply through unconscious communication of attitude and structure. Via the unconscious, a kind of psychological programming of the child’s inner world takes place, for good or ill. It is not what the parent says, but what the parent is and does, that has the greatest impact on the shape the child’s inner world. The family is the child’s adaptive environment, and much of this world’s emotional tone enters the child’s inner world by introjection.

The testing and challenging of physical and psychological boundaries continues throughout the first stage of individuation. Adolescence, which for most of us falls within this stage, is a transitional time when physically, and to some extent psychologically, a person is ready to leave the nurturing/containing environment and enter the next stage of individuation. In modern first world societies, however, this is complicated by educational and training requirements that often prolong the containment stage to a significant extent. An adolescent of 15 or even 18 is nowhere near being able to take on the tasks and responsibilities of adulthood in modern societies. This prolongation of the first stage of individuation creates the specific problems and attitudes so characteristic of adolescents in these countries: impatience, rebelliousness, feelings of inferiority, being marginalized, and frustration. Ready to leave the world of childhood but not yet prepared for the tasks of adulthood, they are truly “betwixt and between.” The adult personae that initiation rituals provide in traditional societies are withheld from adolescents in modern cultures, and the dependent state of childhood is artificially prolonged far beyond its natural physical and psychological timeframe. Schools and colleges are the holding pens and containers devised by modern cultures for adolescents and post-adolescents who need to have more time to mature and to become acculturated and ready for successful adaptation to the demands of work and family that are shortly to fall upon them.

THE ADAPTING/ADJUSTING STAGE OF INDIVIDUATION

While the mother occupies the symbolic center of the first stage of individuation, the father assumes this position in the second stage. This transformation comes about not by usurpation but gradually and through psychological necessity. The father is needed by the growing ego to gain freedom from the nurturing containment offered by the mother and to instill the rigor of functioning and performance demanded for adaptation to the world. The father introduces anxiety to the ego, but ideally in amounts that can be mastered by increasing competence.

Again it is necessary to understand the terms “father” and “patriarchal” (Neumann) symbolically and metaphorically rather than literally and sociologically. Where the first stage of individuation is characterized by containment and nurturance (the Garden of Eden), the second stage is governed by the law of consequences for actions taken (the reality principle) and by the constant demand for performance and achievement in the wider world. In the second stage of individuation, the person is exposed to a world in which standards of performance are paramount and consequences for behavior are forcefully and implacably drawn. A person who is living fully in this type of environment of expectation and conditional regard has entered the “father world”. It is no longer a world in which unconditional love is the norm, but rather one in which strict and even harsh conditions are imposed upon the distribution of all rewards, including love and positive regard. This is not the world as ideal but the world as real. The ego is required to become realistic about itself and about the world at large. This means fitness and competition.

In truth, the reality principle is typically introduced into the life of children long before they leave the containment stage, but there, ideally, it is introduced in doses that are moderate and therefore tolerable to the young and vulnerable ego. The containing environment provides a protective screen that removes the harsh and potentially damaging aspects of reality. The demands for performance and achievement should not be brought to bear too forcefully or too soon in life. If this does happen, the child’s ego can be crushed or convulsed with anxiety. Against severe threats such as these, the psyche will erect primitive defenses to guard against annihilation. On the other hand, if too few demands for achievement and performance are introduced into a child’s Garden of Eden, and if consequences for behavior are not drawn, the ego does not become accustomed to dealing with stress and tension. It remains underdeveloped, and hence will be unprepared later for the demands and expectations characteristic of the next stage of individuation. A moderate amount of frustration and tension, dosed out at the right times and in the right amounts, is growth promoting for the ego. Jung believed that the ego develops through “collisions with the environment”, and Fordham introduced the notion that the ego develops through cycles of de-integration and re-integration. Both notions feature the element of optimal frustration.

Typically the demand for some measure of control and performance begins already in the first years of life with toilet training and weaning. This may be introduced slowly and subtly, but the timing coincides with the child’s ability to make the necessary adjustments. Demands for performance pick up with schooling and gradually increase in seriousness and consequence as a child passes out of primary school into secondary school. The father becomes a more important figure, symbolically speaking, after the early years of childhood have passed. By the time a child reaches high school and college, the adaptive environment induces a good bit of anxiety, and the young person becomes aware of and responsive to the demands of a less forgiving world. Consequences become more life shaping and determinative of action and behavior. In some countries, the academic tests taken around the age of 13 are decisive for a person’s entire career. Grades and academic performance have life-changing consequences for almost all children, and under the pressure of this awareness there comes the realization that the world will not continue to be the nurturing container that one knew as an infant and a young child.

The decisive passage from the first stage of individuation into the second takes place over a period of time, typically between the ages of early puberty and early adulthood (ages 12-21) in most modern societies. This may be earlier in exceptional cases, and it is later for people who prolong their education into graduate and post-graduate studies. Schools are partially matriarchal holding environments and partially patriarchal adaptive ones. Their job is gradually to prepare a person for life beyond school. (For some people, of course, this does not happen. They may ignore school and drop out of its programs before they reach any degree of real competence, or they may stay in school all their lives, as perpetual students or teachers.) As bridging institutions, schools play the archetypal role of the paternal parent to a growing child, whose job it is to help the child leave the family container when the years appropriate for nurturing are over and adapt to the demands of adult life in the larger world. This is the role fathers play in traditional cultures for the young men who come of age and need to be introduced into the social structure at a new level. Mothers play a similar role for daughters, who are given new and larger responsibilities and taught the skills of womanhood as they come of age. In modern societies there is no distinction of this sort between sons and daughters. Today both genders go to school with the idea of preparing for a life of work in the world outside the home. In addition, both genders are expected to accept the responsibilities of house holding and childrearing. The division of labor between women and men, while still often present to a degree, has been considerably blurred in modern life.

The completion of the passage from the containment stage (childhood) to the adapting/adjusting stage of individuation (adulthood) is, of course, fraught with crisis and emotional turmoil. The largest psychological obstacle lying in the way of making this passage is what Jung discussed under the rubric of the incest wish. Disagreeing with Freud that the incest wish was concretely a wish to have sexual relations with one’s closest family members, especially the contrasexual mother and father, Jung interpreted it as the wish to remain a child, to stay in the containment stage of life. The incest wish is the wish never to grow up, to live in a Garden of Eden forever. Peter Pan speaks for this attitude when he announces with vehemence: “I’ll never grow up, I’ll never grow up!” and refuses the transition from playful boy full of fantasy to reality oriented adult. What is required psychologically to overcome this desire to remain a child is the appearance of the “heroic,” a surge of ambition and energy that pushes one out of the security of Eden to meet the exciting challenges offered by the real world. The hero is the archetypal energy that kills the dragon (i.e., “the incest wish”) and frees the princess (i.e., “the soul”), for the sake of going forward in life. The hero asks for and takes up the challenges of real life with an abundance of confidence that many find unrealistic and almost death defying. The hero shows the confidence, call it bravado, to face up to the father and meet the challenges of the patriarchal world. An inner identification with a hero figure frees the ego from the pull towards regression and towards the comfortable earlier dependency on the “mother” and energizes it to meet the tasks and challenges of adaptation to reality. When a person comes to the conclusion that reality offers greater and finer rewards than fantasy, and that reality can be mastered, that person has passed from the first stage of individuation to the second.

Reality must be understood as the whole world of psychological, physical, social, cultural, and economic challenges facing an individual in life, many of which lie beyond anyone’s control. To deal with reality means that one faces up to all the issues that present themselves from without and within – love and death, jobs and career, the weather, sexuality, ambition, other people’s expectations, the body with its weaknesses and tendencies to succumb to illness, the consequences of smoking or alcohol abuse, on and on. It means recognizing that one lives and participates in a world filled with uncertainty and hazard, and that one’s area of mastery and control is seriously limited. The hero gladly and even joyfully attacks the problems posed by reality with the confidence that whatever dangers may lurk, there must be some way to surmount them. Every problem has a solution, the hero believes. As the ego sets forth on the hero’s journey, it soon enough discovers that in this stage one comes into a world of work and taxes, of pension plans and insurance policies, of long-term relationships and family responsibilities, of success and failure as judged by others, and of often intractable problems with no clear-cut solution. This is what must be faced, adapted and adjusted to, and invested in during the second stage of individuation. This is life outside the Garden of Eden.

Many people shrink away from this because of early psychological traumas that so severely handicap their capacities to cope with anxiety that they can never bring themselves to face reality fully. Moreover, there is a natural enough resistance to facing harsh reality, and the ego’s defenses push it away. Some people procrastinate and delay so long, and are allowed to do so by extended nurturing environments and circumstances, or by trickery and subterfuge and self-deception, that it becomes embarrassing and nearly impossible to face this transition later in life. This delay produces what Jungians call the puer aeternus (or puella aeterna, for the female version) neurotic character type. For one reason or another in these people, the hero has never arrived on the scene, or the ego has not identified with a hero figure and its energy, and dependency (conscious or unconscious) on nurturing and containing environments, real or imaginary, has been prolonged into adulthood and even old age. The incest wish goes unchallenged to any serious degree, and the threatening father looms too large and fearsome. The psyche stagnates as a result. A sort of invalidism takes hold, as the person, fearing exposure, challenge, and the normal problems of coping with life, shies away and falls back. The ego remains “in the mother”, symbolically speaking, sometimes even literally acting this out by never leaving home. In these cases, one wonders if there is any individuation beyond the first stage. These people tend to remain childish throughout life. They may be harmless, but they also contribute little. Their potentials remain just that, potentials; they are not actualized. They are always just about to write the great novel but can never bring themselves to the point of putting real words on real paper.

Many of the character disorders described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DMS IV) have their origins in the failure to separate successfully enough from the containing world of childhood. The borderline personality disorder, for example, seems to stem from remaining stuck in a love/hate relationship with the mother that is typical of children in their early years: now a person succumbs to fusion states of dependency upon maternal others, now he or she attacks them and tries to separate from them with violent gestures of hatred and disdain. This is a person who has not managed to accomplish the transition process from stage one to two and is repeating the drama of separation from the mother endlessly with significant maternal others throughout an entire lifetime. The narcissistic personality disorder also derives from being stuck in the containment stage of individuation, in that a driven need and demand persists that significant others do nothing but offer adoration and mirroring. People with narcissistic personality disorders long to remain the adored baby forever, performing for enthralled audiences who never utter a critical word or render a judgment on their brilliant performance. Their lives are full of open wounds and suffering because the world outside of the contained space of childhood is not set up to accommodate their needs to be seen and totally admired.

Psychotherapy, as it is usually set up and practiced, lends itself to the impression that it is primarily a nurturing/containing environment reminiscent of the containment stage of development. The therapist typically accepts and supports a patient, withholds judgment, and offers more or less unconditional positive regard and mirroring. Many people who enter therapy, it must be said, come in so beaten and bruised by the slings and arrows of harsh reality that they need a respite, at least for a time, in order to recover their sense of balance and self-worth. If they are deeply damaged from early childhood abuse and trauma, they will repeat the struggles of psychological birth and development in the therapeutic relationship, fusing with the therapist as infant with mother, then struggling to free themselves from the therapist in the way of the borderline who cannot make this transition, or desiring endless amounts of adoration and mirroring from the all embracing and accepting mother-like therapist. In these cases, it is the therapist’s main task to help these people gradually make the transition from the mother world to the father world. In small doses, the therapist administers, consciously or unconsciously, deliberately or accidentally, the collisions with reality that strengthen the patient’s ego and can help to prepare it for the world of adult functioning if these breaches are handled sensitively. From nurturing/containing mother, the therapist changes to another kind of person, a symbolic father, who helps the patient bridge to the world of achievement, work, struggle, competition, and interpersonal competence.

THE CENTERING/INTEGRATING STAGE OF INDIVIDUATION

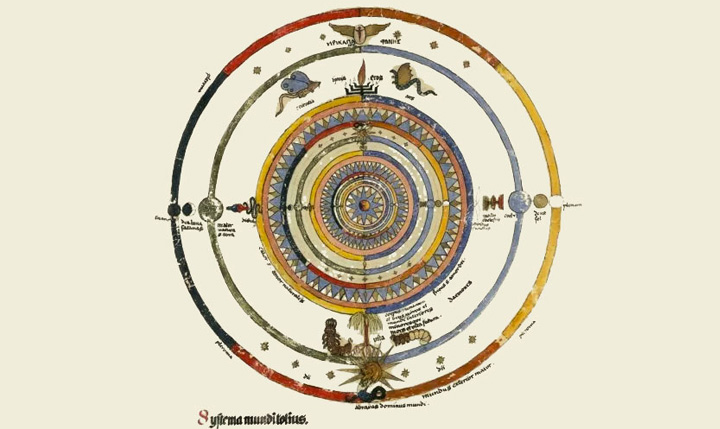

The most significant and interesting contribution of Jungian psychology to the idea of psychological development is what it says about the part of life that follows the second stage of individuation. This is where most other psychoanalytic theories stop. What is still left to do, they might ask, after a person has successfully passed over from the attitude of dependency upon nurturing environments in the first stage of psychological development and has taken up the responsibility of living like an adult in a world of other adults in the second stage? Is there anything more beyond the psychologically advanced stage of entering the father world of adaptation and adjustment and being willing and able to cope with reality? For the Jungian psychotherapist the answer is “yes”, because in fact many people enter Jungian therapy in the second half of life looking for something more than fine-tuning of their patriarchal attitudes and the further elimination of residues of childish complexes. They are often successful adults who have held jobs, raised families, succeeded in reaching many of their goals, and now wonder if this is all there is to life. It is at this point that Jungian reflection on the individuation process in the second half of life becomes relevant. This is the phase of psychological development described classically by Jung in such works as “A Study in the Process of Individuation”, when mandala symbolism, the religious function, and the search for individual meaning become important.

The task in this stage of life, if all has gone relatively well in earlier phases, is not to become a responsible member of the community and a relatively independent and self-sufficient personality (this has been achieved in the second stage), but rather to become a centered and whole individual who is related to the transcendent as well as the immediate concrete realities of human existence. For this, another level of development is called for.

The first separation was from the mother, initially from her body (the first birth), then from her nurturing parental psyche (a second birth). At that point the psychological individual stepped forth into the world. Now there is another passage, a third birth, when the ego puts away the primary importance given to the achievement of adaptation, which calls for conformity to the standards and expectations of the collective (the world of the “fathers”), and embarks upon the journey of becoming an individual. The second stage, a stage of conformity, is often entered, paradoxically enough, by violent acts of adolescent rebellion, undergirded by the energy of the hero archetype. The adolescent breaks out of the parental container with determined force. The third stage, on the other hand, is usually entered into with a rather depressed and questioning attitude, as a person in the middle of life begins to shed the trappings of conformity and enters slowly and often painfully into a process of becoming born anew as a whole and integrated individual. Sometimes this stage is entered as the consequence of tragic loss that shatters fixed collective assumptions. Generally synchronicity (defined by Jung as “meaningful coincidence) plays an important role in the entry into and in the ongoing process of individuation in the third stage.

Entering the stage of centering and integrating means gradually abandoning the previous collective definitions of identity and persona and assuming an image of self that emerges from within. Of course this does not mean leaving collective reality behind. Social reality does not disappear from the ego’s horizon or concern, but coping with it and adapting to its demands absorb less energy. There is a shift of interest and emphasis, toward reaching out to dimensions of living that have less to do with survival and more to do with meaning. Spiritual life becomes more crucially important and individualized.

Much of the identity that is established in the second stage of individuation is derived from collective images and stereotypes, also from parental models. The persona assumed by the ego in the second stage is a structure offered by society and made of a socially constructed set of elements that more or less suit the individual. Personality in the second stage of individuation is largely a social construction. This persona is highly useful for adapting to cultural imperatives and expectations. In the third stage, the ego, which has taken on this persona and largely identified with it, begins to draw away and create a distinction between a true inner self and the social self that has been dominant. As the light between these two psychological structures widens, an element of choice enters with respect to what kind of person one is and is going to become. This new person is more unique and individual, less a social construction.

This does not mean that one can now become anything, or anyone, one wants to be or can imagine. Rather, the truth is that an underlying structure of the psyche – called by Jung the Self (capitalized to denote its transcendence and essential difference from the ego) – comes into play in a new way and takes over the dominant position formerly held by external authority, by the voice of reality and by the “father” and the social persona. The ego now begins to answer to an inner demand and call to obedience from the psyche, rather than primarily to an outer one derived from authorities in society. The new structure that emerges from the inner world of the psyche, in the form of dream images, intuitions, inspirations, remembered ambitions, fantasies, and a strong impulse toward personal meaning, gradually destroys and replaces the persona. Working to live and to survive is no longer sufficient; one must now find something that is worth living for, and this new direction must be tailor made to fit the individual. In fact, it grows out of the individual who is deeply and constructively individuating in the second half of life.

For someone entering upon this stage of development, psychotherapy is quite different from what it is for people who have not made it through the first two stages. While everyone, no matter how developed or mature, shows some residual elements from the earlier stages of development – some borderline and narcissistic features, some degree of participation mystique with others and the environment, some lingering childishness and puerile qualities and defensiveness – these are not the paramount issues in therapy with a person in the third stage of individuation. What is central is, first, separating from the identification with the persona formed in the second stage, and then finding a personal center, a point of inner integrity that is free of the stereotypes of collective culture and based on intimations of the Self. What is aimed for is a degree of integration of the inner opposites inherent in the Self, which allows for striking a vital balance in ones everyday life. Jung speaks of integrating the shadow and relating in a new conscious way to the anima or animus.

Transference is fundamentally different, too, in the psychotherapy of people who are entering or pursuing further the third stage of individuation. The therapist is not consciously or unconsciously related to as nurturing mother or guiding father. Instead, the therapist is typically seen (truly or not) as a wisdom figure, as someone who has achieved individuality and wholeness and relates personally to the Self. This projection is cast upon the therapist because this is the unconscious content that the patient needs and must find a model for somewhere in the world at this stage of life. That job lands at the feet of the therapist. People look for, and seem to find, the models they need for their further growth in their therapists, and an image of psychological wholeness is what is now required by the psyche.

A wisdom figure is someone who is seen to have arrived at an inner center and lives out of the resource found there. It is not necessarily someone who has all the answers to life’s concrete problems. It is a person in whom we see containment of the opposites, who is able to remain intact and balanced in even the most splitting and tension-ridden situations, who maintains an even attitude of connection with others but also detachment from ego preferences. It is a person who has found the Self and lives in relation to that inner reality rather than seeking approval from others or being possessed by desire and attachment to egoistic goals. Most importantly, it is a person who shows spontaneity, freedom, and a distinctive personality. This person is vivid and displays a sense of uniqueness based upon having made many clear individual choices in life.

This image is what is found in the transference projection. Much of it is, of course, a projection based on unconscious patterns that are emerging in the field between patient and therapist. One can think of it as a sort of idealizing transference, but one that is grounded in the archetype of the Self rather than in the unconscious mother or father images.

The goal of this third stage of individuation is the inner union of pieces of the psyche that were divided and split off by earlier developmental demands and processes. In this stage of integration, a strong need arises to join the opposites of persona (good person) and shadow (bad person), of masculine and feminine, of child and adult, of right brain and left brain, of thinking and feeling, of introversion and extraversion. All of the undervalued pieces of potential development that were earlier separated from consciousness and repressed in the course of the first two stages of individuation, so that one could grow an ego and enter into relation to the world of reality in an adaptive way, now come back for integration. In those first two stages one typically becomes a certain psychological type, one identifies with one gender and one gender preference, one adopts a certain persona from among those offered by family and wider culture and identifies with it. In the centering/integrating stage, on the other hand, one reaches back and picks up the lost or denied pieces and weaves them into the fabric of the whole. In the end, nothing (or very little) that is human is foreign to the Self. And as the ego approximates the Self, it too feels less alienated from all of humanity and from the profound complexities of reality. In short, one becomes more accepting of complexity within and without.

CONCLUSION

Individuation is sometimes confused with individualism. To some extent these two concepts overlap in meaning, but individuation is in fact much broader in that it is not limited to emphasizing only the ego. Individualism often ends up being a kind of narcissism, centered on the importance of the ego and its rights and needs. Thus it is correctly judged to be an exaggeration of normal and healthy selfishness. Individuation, on the other hand, includes a large amount of ego development and selfishness, but it does not leave off with this. It goes on to include and integrate the polarities and complexities within and without. It does not ignore the importance of altruism and relationship, but rather includes these elements centrally in its program. It fosters both self-regard and broad social interest in that it focuses on the Self (not the ego), which is common to all humanity. The individuality that arises from the third stage of individuation is made up of a unique collection of common human elements embodied in one particular life, and this one life is not cut off from others or made more important that any other life on the planet. It is simply affirmed as one experiment in human life that is unique because of its precise position in the common matrix.

References

Adler, G. 1961. The Living Symbol: A Case Study in the Process of Individuation.

Toronto: McClelland & Stewart.

Beebe, J. 1992. Integrity in Depth. College Station, TX.: Texas A & M University

Press.

Edinger, E. 1972. Ego and Archetype: Individuation and the Religious Function of

the Psyche. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Fordham, M.1969. Children as Individuals. London: Hodder & Stoughton.

Henderson, J. 1967. Thresholds of Initiation. Middletown, Ct.: Wesleyan U. Press.

Hillman, J. 1977. Revisioning Psychology. New York: Colophon Books.

Jacobi, J. 1967. The Way of Individuation. London: Hodder & Stoughton.

Jacoby, M. 1985. The Longing for Paradise. Santa Monica: Sigo Press.

________. 2000. Jungian Psychotherapy and Contemporary Infant Research. London:

Routledge.

Jung, C.G. 1967. Symbols of Transformation. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton U. Press.

___________. 1966. Two Essays on Analytical Psychology. Princeton, N.J., Princeton U.

Press.

___________. 1968. “A Study in the Process of Individuation”. In Collected Works,

Vol. 9/1, pp. 290-354. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton U. Press.

Kalshed, D. 1996. The Inner World of Trauma. London: Routledge.

Neumann, E.1955. The Great Mother: Analysis of an Archetype. London: Routledge &

Kegan Paul.

_________. 1954. The Origins and History of Consciousness. London: Routledge &

Kegan Paul.

Samuels, A.1993. The Political Psyche. London: Routledge.

Schwarz-Salant, N. 1989. The Borderline Personality. Wilmette, IL.: Chiron Publications.

Stein, M. 1998. Jung’s Map of the Soul. Chicago: Open Court.

_______. 1983. In Midlife. Dallas: Spring Publications.

_______. 1998. Transformation: Emergence of the Self. College Station, TX.: Texas

A & M University Press.

Von Franz, M.-L. 1964. “The Process of Individuation.” In Man and His Symbols(by

C.G.Jung, et. al.). Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday

________. 1977. Individuation in Fairy Tales. Dallas: Spring Publications.